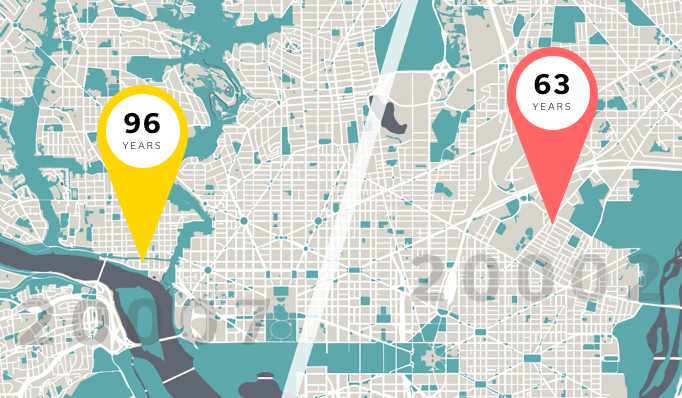

Two 60-year old women live 10 miles apart in the Washington DC area. They’ve both been prescribed beta-blockers for high blood pressure, both have family histories of Type 2 diabetes, and have missed their last few annual check ups. What should their care plans look like? Should they be different?

Clinically, they’re spitting images of each other. However, one piece of data — their zip code — can dramatically tilt the equation. Turns out, they face radically different life expectancies (63 versus 96 years), just based on the difference in their geographic locations. This 33 year life expectancy gap can be chalked up to differences in income level, education level, and access to grocery stores with fresh food.

A decade of EHR use has generated a treasure trove of clinical data. An EHR can tell the full story of a patient’s care, and we’ve built advanced tools to make sense of it all: clinical decision making aids, population health segmentation tools, and automated billing and coding assistants.

However, the never-ending quest to create clinical data models belies one fatal fallacy: clinical data doesn’t tell the whole story.

Prescribing the right dosage of blood pressure meds doesn’t matter if a patient can’t understand the label. Monitoring glucose levels isn’t helpful if the only sources of food are corner stores and fast food joints. Appointment reminders are meaningless if it takes 2 hours and 3 bus transfers to get to the clinic.

These factors, the social determinants of health, determine 80% of a patient’s overall health. The best evidence-based care plans won’t work if we can’t get the patient to the starting line.

This has massive implications for healthcare — treatment within the four walls of a hospital can only do so much. It doesn’t matter how well an ED doc can stitch a patient up if the patient is only going to return home to an unstable environment and end up in the hospital a few weeks later. A patient’s health is the result of a complex interaction of social structures and behavioral patterns, spanning everything from genetics and biology to social circumstances to physical environments.

The industry is waking up to this reality. Hospitals have started partnering with community-based organizations, trying to increase patient access to services and resources they might need. CMS established the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model last year to create better linkages between clinical and community providers for high-risk Medicare and Medicaid patients. CMS also maintains several databases that track racial and ethnic disparities in clinical care.

These are good starts, but their top-down approach makes it difficult to reliably apply these findings to clinical care. A CMS community resource database, for example, can’t tell you that the patient in front of you is a single mom with three kids who is struggling to get to the pharmacy to pick up her prescription because she’s constantly juggling child care and work responsibilities. Only she can.

To treat patients holistically, taking their full clinical, demographic, and social profile into account, hospitals need to adopt a bottom-up approach and get the information straight from patients.

Surveys like the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE) ask the simple but important questions, like the following:

-

What is your housing situation today?

-

Has lack of transportation kept you from medical appointments, meetings, work, or from getting things needed for daily living?

-

How often do you see or talk to people that you care about and feel close to?

Imagine knowing the answers to these questions for every patient that walks in for treatment. Each answer could have crucial implications for their patient journey and adherence to their care plan. Their housing situation might give us clues about how their physical environment might have caused or might worsen their medical situation. Access to transportation determines how likely a patient will be to pick up their prescriptions or attend follow-up appointments in the future. A patient’s social network can say a lot about whether someone will be there to provide emotional support and help keep the patient on track with their treatment plan.

The key to collecting this kind of information is doing so in a conversation. Handing a patient another form to fill out misses a critical opportunity to connect meaningfully with the patient. Done well, a conversation about the social determinants of health can reassure a patient that their care team cares about their particular story and healthcare journey.

The tradeoff, of course, lies between efficiency and effectiveness. Paper forms require less physician time and can efficiently collect standardized sets of information, but may not reveal a patient’s full story. Face-to-face conversations between the physician and patient yield a depth of details about a patient, but they take time.

To address this tradeoff, hospitals should start leveraging conversational technology to connect with patients. Chatbots can add the human touch while holding dozens of concurrent conversations, allowing hospitals to give patients the care they deserve with maximum efficiency. Better yet, conducting these conversations through a digital medium allows for seamless integration with EHRs, allowing physicians to immediately capitalize on the information.

As the industry moves towards more value-based and risk-sharing contracts, providers can’t afford to leave outcomes outside the hospital to chance. To be successful, providers must collect, understand, and utilize social determinants of health across their full patient populations. This fundamental shift is the only way for us to truly understand patients and their unique journey through the healthcare system.