Awareness of diversity and inclusion has risen across our entire society over the past few years. The combination of the coronavirus pandemic and social justice movement shed a bright light on healthcare. Among many of the socioeconomic and racial disparities that COVID-19 highlighted, one of the most significant was the need to increase diversity in clinical trials.

Clinical trials have struggled with diversity issues for decades. Most recently, in both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine trials, black patients represented just 10% of the participants, despite constituting over 13% of the US population.

Diversity in clinical trials isn’t just a nice-to-have — it’s foundational. It directly impacts health equity, access to new patient populations, and patient trust in pharma manufacturers. In fact, a recent Accenture report showed that 18% of surveyed patients would increase their trust in pharma companies if they had increased patient diversity in clinical trials.

COVID-19 vaccine trials have highlighted the general lack of Black and Hispanic participation in trials, but diversity challenges go much deeper than most of us realize.

In the process of diversifying clinical trials, we continue to under-discuss Asian American representation in clinical trials and how to address specific health disparities. A stand-out example within the Asian American community is the issue of liver cancer and access to appropriate clinical trials.

Studies have shown that nearly 62% of Asian Americans have no knowledge of clinical trials. Authors of one study pointed out that having some guarantee of treatment effectiveness and lack of side effects can facilitate participation, and that providers play a key role in informing patients about clinical trials.

Carrying a Disproportionate Disease Burden of Hepatitis B

Today, Asian Americans account for 58% of individuals with chronic Hepatitis B despite making up only 6% of the population. Hepatitis B is the leading underlying cause of liver cancer. As such, Asian Americans are twice as likely to develop liver cancer as non-Hispanic white Americans.

Today only a few drugs are approved for treating liver cancer. With liver cancer now becoming the fastest increasing cause of cancer death in the U.S, personalized liver cancer drugs are quickly being developed. There are over 92 liver cancer trials that are currently recruiting patients across the US.

Despite this disproportionate disease burden, many of the same challenges pharmaceutical manufacturers and clinical research organizations have seen in engaging underserved populations repeat in engaging other minority groups. Interacting with patients through a trusted health care provider, making materials available in their own language, and being sensitive to cultural beliefs can entice more patients of all backgrounds to participate in trials.

For people with early-stage liver cancers who get a liver transplant, the 5-year survival rate is in the range of 60% to 70%. People who are not diagnosed as early and have not received a liver transplant have poorer survival rates: the general 5-year survival rate is 20%. As the waiting list for liver transplants becomes increasingly long, pharmaceutical intervention seems like the easier path to take.

Liver cancer is a serious concern. Can Asian American patients be engaged effectively? Can liver cancer drug manufacturers diversify their trial population? How might drug manufacturers and contract research organizations engage with Asian American populations through community-based health centers or patient advocacy groups?

Increasing Asian American Participation and Awareness with Technology

There is a clear opportunity for liver cancer drug manufacturers to work with patient-centered groups like the HepB Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and academic medical centers like the Asian Liver Center at Stanford, and the Center for Asian Health at Temple University to engage patients around liver cancer trials.

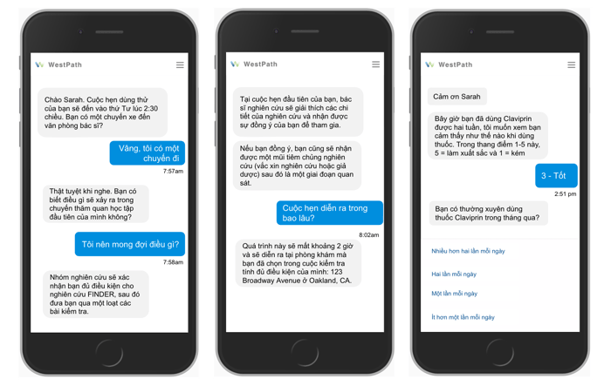

One route manufacturers and research organizations might consider is using advanced conversational technology to drive better engagement. Reaching out to patients through low-friction, culturally fluent, login-less messaging directly on their mobile phones to assist across their entire journey up to, through, and after the trial has shown success in other trial diversity initiatives and there’s no reason to believe it won’t work with Asian Americans.

Here’s how it might work in a trial for a promising new treatment for liver cancer. Patients that have registered with academic medical centers, expressed interest to their providers, or signed up with patient centered groups could interact with smart digital assistants in culturally appropriate, plain-language summaries about clinical trial opportunities. Patients could further use messaging on their phones to learn about how a clinical trial works, answer questions they might have about the medication or trial itself, and refer other members of their communities into the trial if they think it might be of interest.

Providers could review analytics to get a better sense of the patient’s trial review progress, and help sponsors proactively address patient questions. To increase Asian American representation in clinical trials, quickly polling participants around questions such as the best time to engage, satisfaction with trial resources/transparency (e.g., workers were not culturally sensitive), and issues with transportation to trial sites can help sponsors.

A comparable use case was the BRCA Founder Outreach Study (BFOR) led by Memorial Sloan Kettering. It was a fully decentralized registry trial to direct members of the Ashkenazi Jewish population towards BRCA mutation testing. Over the course of this trial, 4,000 participants interacted with smart mobile chatbots to enroll, consent, participate, and adhere to the steps that were outlined across the entire trial. BFOR investigators were able to drive efficiency in the trial while simultaneously maintaining cultural fluency such that 100% of consenting patients made it through the trial.

Diversity is a large complex problem that has no silver bullet solution. It will require iterative work. Conversational AI can help with diversifying clinical trials, and enabling improved recruitment and enrollment in liver cancer trials for Asian Americans. With 92 clinical trials currently recruiting, hopefully patients can find a trial that fits their needs.